EDMO: "Any Response to Disinformation Needs to Respect Freedom of Expression"

© EDMO

Today, many associations working in the science, health or education sectors are especially vulnerable to widespread disinformation, public distrust and the specific vulnerabilities of digital media. Their projects and task forces support the verification of sectoral studies, quality information and liaison between multidisciplinary expert communities. However, as in civil society, associations are also subject to the impact of misleading content, fabricated data and unreliable sources.

The European Digital Media Observatory (EDMO), the EU’s largest interdisciplinary network on this subject, brings together fact-checkers and academic researchers with experience in the field of online disinformation, social media platforms, journalism and media education professionals. Paula Gori (pictured below), EDMO Secretary General and Coordinator, explains how transparency and media literacy can serve as benchmarks not only for journalism, but also for policy-makers and for new guidelines of science communication.

1) With AI tools shaping how people access news, how can we protect general and less tech-savvy users from biased content, clickbait, or reality-altering narratives?

1) With AI tools shaping how people access news, how can we protect general and less tech-savvy users from biased content, clickbait, or reality-altering narratives?

It is important to highlight that AI is not only used to produce disinformation, but also to distribute and spread it. On the users’ side, media literacy plays a key role. As with education in general, it needs to be inserted into a specific strategy. What the EU can do is work on support and guidelines with experts to combat disinformation and promote digital literacy through education and training. At Member State level, debates vary, although the general observation is that media literacy should be a curricular activity in schools in all countries. EDMO is doing a lot of work on media literacy.

Let me mention just two examples. The first is aimed directly at citizens. In particular, we ran the #beelectionsmart online campaign ahead of the 2024 European Parliament elections, and another one, both offline and online, called #beonlinesmart, in all Member States in their respective languages. The second example concerns media literacy initiatives themselves and, in this regard, we have published guidelines for eff ective media literacy initiatives. The underlying logic is that it is not just a question of organising these initiatives, but also of guaranteeing their quality, effectiveness, impact and sustainability.

2) How is EDMO tackling fast-spreading polarised narratives there, and how can organisations support fact-checking and media literacy in these spaces?

Because of its role and structure, EDMO can on one side detect and analyse disinformation narratives, trends, actors and techniques and on the other act with media literacy campaigns, as those mentioned above. In general, resilience initiatives shall take place both on the platforms themselves and offline like in schools, libraries, workplaces, clubs, etc. Both initiatives depend however on a number of factors which include funding, political and business willingness, an education strategy, identification of the target audience, and impact evaluation. When it comes to younger generations, but not only, any initiative shall be tailored according to the culture, languages, traditions, education, media diet, and the history of a given country. The difference between urban and rural areas shall also be taken into consideration. Public-private partnerships in funding these initiatives are fundamental in the interest of citizens, the information integrity and the democratic process.

3) How can organisations spot early signs that their topics are being targeted by disinformation, especially during elections or high-stakes public debates?

Probably the first sign comes from popularity: the moment a given topic, action, or activity hits the news (or goes viral on social media), and/or stimulates particular interest in society – or a part of it – is also the moment when there is a risk of disinformation. Disinformation, if you will, jeopardises the attention that accurate information is receiving. Elections, for obvious reasons, represent a clear case, but they are by no means the only attractors. Think, for example, of climate change, health (Covid-19 clearly showed this), migration, gender, etc.

“Reporters must make sure that their data, wording and visuals are not presented in such a way that they can be exploited.”

4) How can associations strengthen their credibility and resilience against attacks from pseudo-media sources or coordinated campaigns on behalf of hidden interests?

Overall, prevention plays an important role. Being as transparent as possible and building a strong reputation based on trust is already a good deterrent. It is also important to have an emergency team that can immediately detect and react to any attack. Such a team should work also on preparedness, which includes building the right networks and channels which could be activated in case something happens. It also includes detecting the risks before they create harm, testing the algorithms and mapping the information landscape.

Even so, if an attack happens, it is key to avoid as much as possible information voids, as they become the entrance door for disinformation. If, as happens in times of crisis, organisations do not immediately have precise responses or data, then it is key to be transparent on the uncertainty. This means clearly stating what is known, what was done, what is in place to get the missing knowledge and if relevant what can be done to get protected/act.

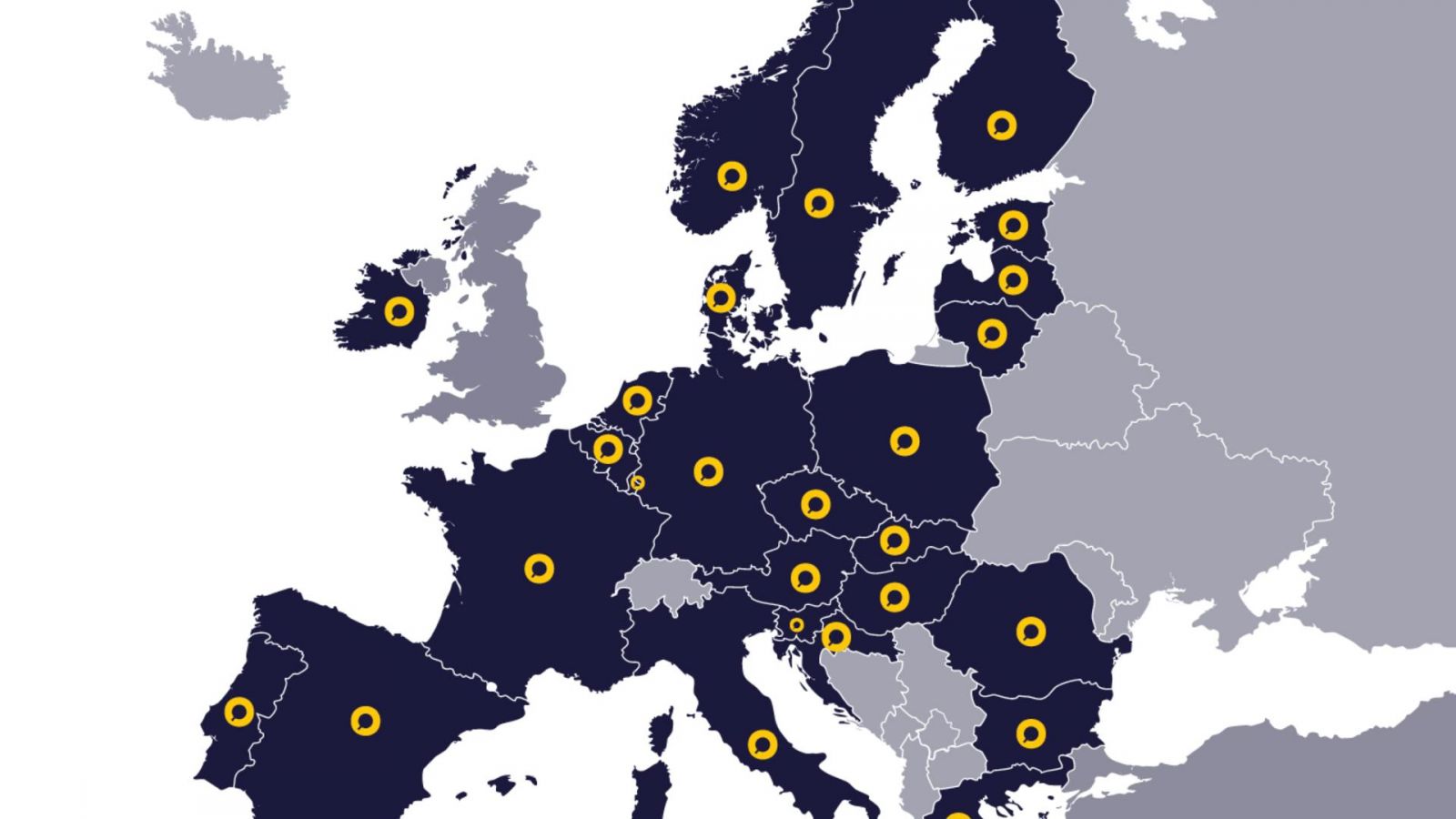

EDMO National Hubs throughout Europe

5) What can associations learn from EDMO’s standards around source verification and transparency?

As a rule, transparency is an excellent choice. On the production side, depending on the situation, there may be transparency on the process, on the output, on the evidence, etc. On the structural side, transparency on funding, resources, organigramme (and when relevant, confl icts of interest) is key. Going back to the specifi c case of disinformation, any analysis of content needs to be transparent both when it comes to the methodology and to the sources, as citizens must be put in the position to trace back how a certain conclusion was reached and potentially share additional sources. Transparency on funding and structure of the organisation behind is also required.

6) How does EDMO manage different national definitions of truth or legal grey areas when responding to cross-border disinformation and polarised media landscapes?

Disinformation, according to EU policy, is false or misleading content which may cause public harm, that is spread with an intention to deceive or secure economic or political gain. In general, this means starting by detecting content, analysing if it is based on facts and if not looking at the intention(s), the techniques, and the actors behind. In jargon, we often refer to disinformation as awful but lawful content. On the other side, any response to disinformation needs to respect freedom of expression. We cannot have a Ministry of Truth, hence the multistakeholder and multifaceted approach in the EU.

It is also key to remind that facts are facts, while opinions are interpretation of facts. The distinction is important, especially when a given piece of content supportive of a given narrative is debunked. To respond to disinformation it is key to identify it and to understand it. EDMO’s key role is building a community of media literacy experts, fact-checking organisations, researchers and policy experts to implement the stakeholder approach. Because we can count on the collaboration with 14 national and regional hubs covering all EU Member States, plus Norway, we have the added value of building possibilities for cross-border dialogue, sharing of best practices, collaboration, cost-efficiency strategies, and complementarity.

“We need media literacy as much in schools as in the workplace, in old people's homes or social clubs.”

7) Even with strict editorial checks, disinformation can slip through. What fact-checking safeguards or editorial practices can help reduce this risk in everyday reporting?

Well, there are two sides of the medal here. On one side, it is important that any output is verified as to ensure that it does not include false information, nor decontextualised data or misleading content. This means checking different sources, when needed inquiring with independent experts, involving peer reviewers, etc. On the other side, reporters should make sure their data, wording and visuals are not presented in a way that they can be exploited. This means being transparent and clear and asking themselves if what they write could be subject to misleading interpretations, if it could be easily negatively taken out of context, if it leaves margin for being manipulated. Overall, what I said above applies here as well: whenever something is still missing evidence, be clear about this and transparent about how you are planning to get to that evidence. Instructions and extra

Powered by Meeting Media Company, publisher of Headquarters Magazine (HQ) – a leading international publication based in Brussels, serving the global MICE industry and association community.